NEW YORK — The nation’s most segregated schools aren’t in the deep south — they’re in New York, according to a report released Tuesday by the University of California, Los Angeles’ Civil Rights Project.

That means that in 2009, black and Latino students in New York “had the highest concentration in intensely-segregated public schools,” in which white students made up less than 10 percent of enrollment and “the lowest exposure to white students,” wrote John Kucsera, a UCLA researcher, and Gary Orfield, a UCLA professor and the project’s director. “For several decades, the state has been more segregated for blacks than any Southern state, though the South has a much higher percent of African American students,” the authors wrote. The report, “New York State’s Extreme School Segregation,” looked at 60 years of data up to 2010, from various demographics and other research.

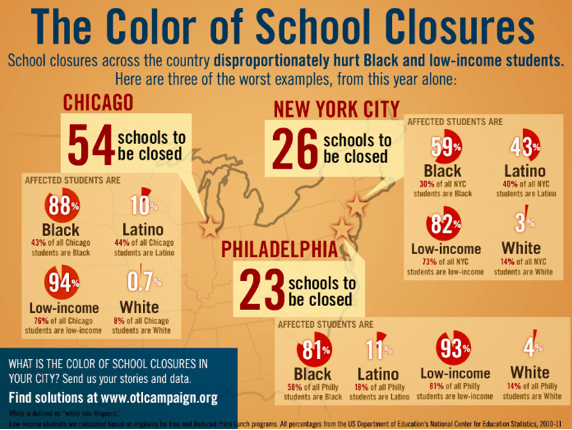

There’s also a high level of “double segregation,” Orfield said in an interview, as students are increasingly isolated not only by race, but also by income: the typical black or Latino student in New York state attends a school with twice as many low-income students as their white peers. That concentration of poverty brings schools disadvantages that mixed-income schools often lack: health issues, mobile populations, entrenched violence and teachers who come from the least selective training programs. “They don’t train kids to work in a society that’s diverse by race and class,” he said. “There’s a systematically unequal set of demands on those schools.”

“Charters are damned if they do and damned if they don’t. If they open in mixed-income neighborhoods as many have tried to, they are accused of abandoning their mission to serve high-needs kids and of trying to inflate their test scores,” said James Merriman, CEO of the New York City Charter School Center. “And when they do serve children in low-income areas — neighborhoods which are historically segregated — they are accused of being too narrow in focus.”

“So instead of focusing on the bogus conclusions of this study,” Merriman continued, “we’re going to focus on providing a great public education to all of our students, no matter where they live.”

Charter schools are publicly funded but can be privately run, and their segregation has long been controversial. Charter schools in urban areas tend to be segregated, in part, because they seek to serve specific low-income communities. Some intentionally cater to one race, with a focus on black culture.

In New York City, charter schools have been the center of a newly-simmering debate, with Democratic Mayor Bill de Blasio overturning the space-sharing arrangements of a few charter schools that had been green lighted by the Bloomberg administration. Though de Blasio recently softened his charter school tone, the announcement that he would alter the space-sharing arrangements of several charter schools run by the Success Academy chain set off a loud and expensive media blitz.

Orfield hopes that all this hubbub means that the city’s charter landscape is ripe for change, and that charters can start focusing on civil rights. “I hope this new multiracial city leadership in New York that wants to take a new look at these things will not just stereotype all charter schools as bad or all public schools as good, but will try to make more schools of choice that are equitable or diverse in both of those sectors,” Orfield said.

Representatives for Success Academy and the De Blasio administration did not respond to a request for comment. The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools said it was unavailable to comment before press time.

How did New York get this way? Forty years ago, according to the report, New York state made “school desegregation … a serious component of the state’s education policy as a result of community pressure and legal cases.” Legal fights in Yonkers and Rochester respectively targeted housing and educational segregation, and resulted in an inter-district transfer program. New York City never saw a lawsuit over school segregation but community leaders “challenged practices and policies that perpetuated racial imbalance and educational inequity across schools.”

But during the Reagan administration, policy shifted focus. New York instead looked to newly popular ideas to improve school quality: charter schools, school choice and school accountability. “By the early twenty-first century, most desegregation orders in key metropolitan areas were small and short-lived due to unitary status, and many programs designed to voluntarily improve racial integration levels, like magnet schools, are now failing to achieve racial balance levels due to residential patterns, a lack of commitment, market-oriented framework, and school policy reversals,” the authors write. And while many New Yorkers involved in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case tried to alter the racial composition of New York’s schools, nothing happened — not even one school in Harlem was integrated.

Orfield argues that despite this turn in education policy, actively pursuing desegregation is still important. “From the benefits of greater academic achievement, future earnings, and even better health outcomes for minority students, and the social benefits resulting from intergroup contact for all students … we found that ‘real integration’ is indeed an invaluable goal worth undertaking,” he wrote.

To help remedy the problem, Orfield suggests emphasizing education policies that mitigate segregation, such as an equal distribution of resources, the building of low-income housing in new communities, student assignment policies that take race into account and having schools report on their diversity. Charter schools, he recommended, should target recruitment and weight admissions to make sure they reach students of different races.

Some contested Orfield’s rhetoric. “I have some sympathy for his goals … but Orfield takes it way over the top,” said Michael Petrilli, executive vice president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Petrilli has written a book on school diversity. “The reality is, a city like New York does have a lot of racially concentrated schools, and that’s because it has a lot of racially concentrated neighborhoods. That fundamentally comes from housing segregation. … We need both these high-poverty schools that are high-performing and we need integrated schools that are high-performing.”